A couple of years ago, I took a bike ride from Slough, heading east – right through London and out the other side to Basildon. I was looking for two important but hidden locations: a data centre belonging to the London Stock Exchange, and another belonging to the New York Stock Exchange. To find them, I followed the line of microwave dishes that connect them – some perched on pylons, others on water towers or tall buildings. These beams of data carry millions of high-frequency financial transactions – and thus billions of pounds – through the air, above our heads, completely invisibly.

Near Heathrow airport, I looked up to see the microwaves passing through two huge dishes atop Hillingdon hospital, a pioneering 1960s centre now suffering – like much of the NHS – from a shortfall in funding. For a rent of a few thousand pounds a year, the machinery of private finance perches on the crumbling infrastructure of the welfare state: all that money, flowing invisibly just a few metres above the patients inside. This is how a difference in visibility translates into a difference in power: those who can see, can understand – and thus shape the world to their advantage.

So how do we begin to understand a world in which the most powerful technologies of our time are so hard to see that most of us aren’t even aware of them?

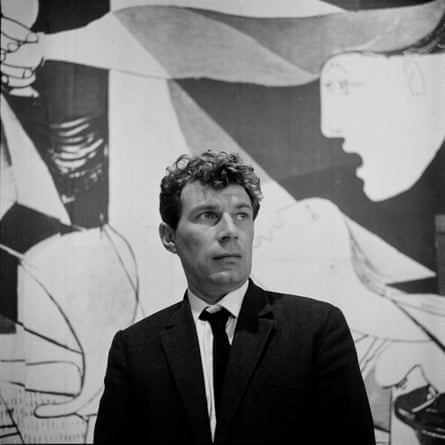

Perhaps we should look to art for guidance. More specifically, to the work of writer and critic John Berger, who didn’t just help us gain a new perspective on viewing art with his 1972 series Ways of Seeing – he also revealed much about the world in which we live. Whether exploring the history of the female nude or the status of oil paint, his landmark series showed how art revealed the social and political systems in which it was made. He also examined what had changed in our ways of seeing in the time between when the art was made and today.

The camera, he argued, had radically altered our relationship with great artworks, by severing the old masters from their original context: “By making the work of art transmittable, [the camera] has multiplied its possible meanings and destroyed its unique original meaning.”

This observation seems even more pertinent today, in our image-soaked culture, where everyone is a photographer, and digital pictures flow endlessly from machine to machine, making up not only the fabric of artistic expression but also social media, digital maps, targeted advertising and surveillance. In a world of fake news and facial recognition technology, many of the ideas in Ways of Seeing have never seemed more relevant. Which is why I have made New Ways of Seeing, a radio series which, like Berger’s original, seeks to answer the most pressing questions in art today: namely, ones around digital tools and the internet.

It’s one of the ironies of the present age that while we feel that everything has changed, our view seems to be unaltered. If you walk down the street, the buildings, vehicles and people all look much the same as in Berger’s heyday. The digital revolution is largely an invisible one – until you start to look closer. The people are mostly talking to themselves, or staring at their hands, and the banks, post offices and libraries are coffee shops, because most of their functions have moved online. As a result, we rarely “see” the digital world as it really is – even as it makes more and more claims over our lives.

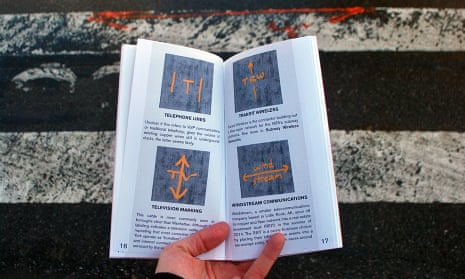

In the first episode of New Ways of Seeing, I meet artists such as Ingrid Burrington and Trevor Paglen, who explore this hidden architecture of the internet. In New York, Burrington takes us inside 32 Avenue of the Americas, an art deco temple to telecommunications dating from 1932, when it was the headquarters of AT&T’s transatlantic network. The atrium contains a grand mural depicting nation calling nation across the telegraph wires – but Burrington also shows us the manholes and markings on the street outside that allow us to read the fibre-optic cables snaking under the city today.

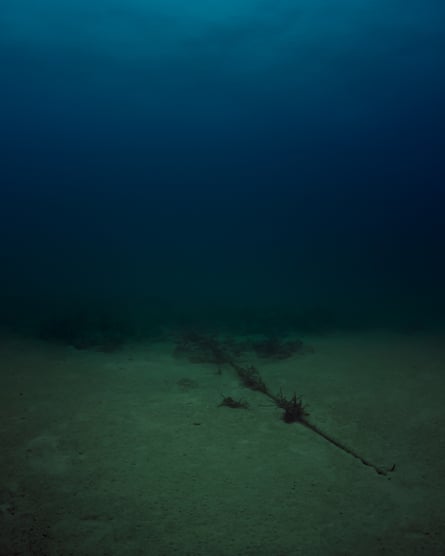

Paglen in turn takes us to the bottom of the ocean, where he photographs the same cables that connect nations today. We’ve got used to hearing about “the cloud”, the numinous neverland where the machines do their unseen work, but this is where it comes back down to earth. Looking at a map of the ocean-going internet, we can see how its real shape maps on to the trading routes of old empires; how former colonies are still dominated by connections to their old rulers, and forms of digital colonialism persist into the present. It’s artists who are mapping these sites in order to try and draw a truer picture of the world today, one so often hidden under glass, buried under the ground, or concealed in lines of inscrutable code.

Berger dedicated one of his episodes to the female nude in western art and the ways women were systematically objectified. A close look at technology today shows that those prejudices have not gone away; instead they’ve been programmed into today’s seeing machines. Among others, we hear from Stephanie Dinkins, an artist building her own artificial intelligence from the stories of generations of women of colour to counter the prevailing biases of recruitment and sentencing systems. We also speak to Morehshin Allahyari, who uses 3D printing to reclaim histories and sculptures destroyed by Isis – and appropriated by western museums.

As Berger wrote in 1972: “We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.” Beneath the surface of the street, and behind the screens of our computers, hide powerful forces that shape all of our lives. To reckon with them requires a new way of seeing: an understanding of the connections between infrastructure and code, state surveillance and corporate power, social prejudice and algorithmic bias, and the environment and computation. It’s a form of seeing vital to understanding the times we live in, and as at every previous time in history, it’s artists who are helping us to forge it.

New Ways of Seeing starts 17 April at 9am on Radio 4 and BBC Sounds.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion